“I feel like a breathing zombie right now,” South African artist Zanele Muholi wrote, following the theft of five years of her work. “Whoever ransacked the place got away with more than 20 external hard drives with the most valuable content I’ve ever produced.” In April, Muholi’s apartment was burglarized, the thief making off with camera equipment and hard drives containing her work on queer lives in South Africa.

Muholi has dedicated her career as a photographer to the African LGBT community, particularly focusing on Black lesbians. Her photographs document the faces and experiences of Black lesbians throughout Africa, providing visibility for a group that is ignored, or made victim to horrific hate crimes.

[Trigger Warning] On her website, Muholi links to a very disturbing video on corrective rape of Black lesbian women. This video reveals a staggering trend in South Africa: “One in every two women in the country can expect to be raped at least once in her lifetime.”

Many black lesbians have been targeted because they exist outside the realm of heterosexuality, outside what is considered normal. For that, they have been beaten, raped, and murdered.

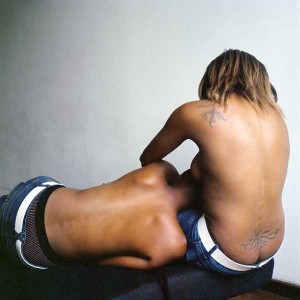

In her Being series (2007), Muholi photographs Black lesbian couples. The primary purpose of this series, Muholi says, is to end “the very stigmatisation of our sexualities as ‘unAfrican’, even as our very existence disrupts dominant (hetero)sexualities, patriarchies and oppressions that were not of our own making.” This series is also intended to increase awareness of and participation in safe sex.

The photographs show the forbidden intimacy between African women. In one photograph, two women kiss. In another, a couple bathes together in a rural township home. By capturing these acts of love and affection on film, and in simple every day spaces, Muholi defies those who would erase or destroy Black women’s same sex sexuality.

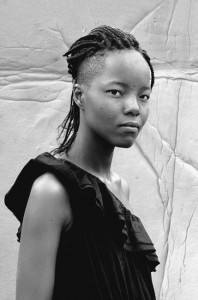

In Faces and Phases, Muholi presents intimate portraits of Black lesbians. She says she took on this project “to ensure that there is black lesbian visibility, to showcase our existence and resistance in this democratic society, to present a positive imagery of black lesbians.” These portraits make their subjects human. These women have dignity and rights. They exist as women who love women, and they embrace their identity in spite of all who wish to change them.

In Faces and Phases, Muholi presents intimate portraits of Black lesbians. She says she took on this project “to ensure that there is black lesbian visibility, to showcase our existence and resistance in this democratic society, to present a positive imagery of black lesbians.” These portraits make their subjects human. These women have dignity and rights. They exist as women who love women, and they embrace their identity in spite of all who wish to change them.

The New Yorker has commented on the theft of Muholi’s work, but most major media have ignored the loss. And truly, this is a great loss for the LGBT community and the world. The theft is assumed to have been a hate crime, as little else was stolen. Gone are photographs that were never shown publicly. Muholi has said, “I am in mourning,” and it seems many members of the international community feel similarly. The loss of Zanele’s work photographing LGBT Africa is a blow to the community, and its history.

However, through this tragedy, hope has begun to offer healing. Though money cannot recover Muholi’s lost work, her indiegogo campaign, started by Palm Wine, a new LGBT Nigeria community group, has raised over $9,000 to replace her lost equipment. The original campaign hoped to hit $5,000, but has by far exceeded that, amassing over $9000 dollars as of last week.

No doubt, many people have been moved by Muholi’s work and wish to see her continue to take photographs despite this devastating loss. There is hope in the support she has been receiving, hope for LGBT Africa’s continued preservation of its history as well.

It’s so sad to see this, but it proves just how powerful Zanele Muholi’s work is. I’m glad she’s moving forward and staying strong. It’s important to see the support from the community standing by her.